Competition | 30.06.2010

Russia looks westward for help with high-tech diversification

Hit by the global financial crisis that led to a sharp fall in trade, Russia has embarked on a campaign to develop its economy away from being simply an exporter of primary commodities, such as oil and gas. President Dmitri Medvedev is staking much of his economic vision on creating a globally competitive high-tech industry.

Part of Moscow's plan is to buy into or even acquire key companies located in technologically advanced, competitive markets such as Germany and France.

Infineon speculation

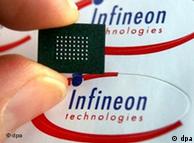

Russia's growing appetite for technology companies is the likely cause of renewed speculation about Russian financial holding company Sistema acquiring a stake in German chipmaker Infineon.

The Russian government, Financial Times Deutschland reported without citing sources, has called on Berlin to let Sistema take a 29-percent stake in Infineon. According to the report, both Medvedev and Prime Minister Vladimir Putin insisted on the plan in talks with German Chancellor Angela Merkel.

Bildunterschrift: Großansicht des Bildes mit der Bildunterschrift: Infineon is on Russia's high-tech acquisition radarSistema has declined to comment, and Infineon is providing little information. A spokesperson told Deutsche Welle the chipmaker "is not currently holding talks" with the Russian company, declining to comment on whether the two firms or the leaders of their countries have negotiated in the past.

Bildunterschrift: Großansicht des Bildes mit der Bildunterschrift: Infineon is on Russia's high-tech acquisition radarSistema has declined to comment, and Infineon is providing little information. A spokesperson told Deutsche Welle the chipmaker "is not currently holding talks" with the Russian company, declining to comment on whether the two firms or the leaders of their countries have negotiated in the past.

In December 2009, Sistema confirmed talks about becoming a partner in a possible investment in Infineon by the Russian state.

Munich-based Infineon already has some operations in the Zelenograd region near Moscow, where Russia's largest semiconductor companies, Mikron and Angstrem, operate facilities.

Already a big user of German technology

Angstrem is already a big user of technology from Germany; the manufacturer, for instance, hired M+W Zander in Stuttgart to build a new chip factory and also took over a production line operated by Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) in Germany.

Another key component of Medvedev's high-tech diversification plan is to create a Russian equivalent of Silicon Valley. The Russian president, who this month toured California's high-tech mecca, intends to build a technology center called Skolkovo outside of Moscow. He hopes talented and entrepreneurial Russians, if given sufficient funding and scientific freedom, will hatch lucrative inventions to help break the country's dependence on gas and oil.

Bildunterschrift: Großansicht des Bildes mit der Bildunterschrift: Merkel and Medvedev are reportedly talking about a Russia-Infineon hookupIt's not as if Russia needs to start from scratch, though. The country has long been a leader in aviation and space technology, where, with the help of advanced microelectronics technology and expertise, it hopes to become a force again. Russia was also at the cutting edge of photovoltaics until the government ceased funding 15 years ago.

Bildunterschrift: Großansicht des Bildes mit der Bildunterschrift: Merkel and Medvedev are reportedly talking about a Russia-Infineon hookupIt's not as if Russia needs to start from scratch, though. The country has long been a leader in aviation and space technology, where, with the help of advanced microelectronics technology and expertise, it hopes to become a force again. Russia was also at the cutting edge of photovoltaics until the government ceased funding 15 years ago.

What's necessary now, most experts agree, is a change of focus.

'Doctoring with intellectual property rights'

"Russia clearly needs to diversify its economy," Fredrik Erixon, director of the European Centre for International Political Economy in Brussels, told Deutsche Welle. "But it's not so much a question of whether it will diversify but how."

Erixon pointed to earlier attempts by Russia to build its own high-tech industry. The attempts failed, he said, for a number of reasons, including a lack of sufficient funding, isolating local companies from foreign competition and, in particular, "doctoring with intellectual property rights."

He also cited a lack of transparency in Russian business as another issue the country will need to overcome in order to build a sustainable high-tech industry.

"Russian companies don't have the corporate governance regulations their counterparts in the West have," Erixon said. "So it can be very difficult to know who's always behind a company, whether it's the government or some other group."

Reciprocity is better

Alexander Rahr, an expert on Russia at the German Council for Foreign Relations in Berlin, believes that while a need for transparency is "correct," he argues that reciprocity, at this point in Russia's economic development, is better.

"Just 20 years ago, private ownership in Russia was forbidden," Rahr told Deutsche Welle, adding that "time is still needed" for Russia to establish the level of transparency expected by western companies.

What's important now, he said, is for Russian companies to be able to buy into western companies and vice versa. "Access to each other's market needs to be the same," Rahr said. "This still requires some political effort."

Author: John Blau

Editor: Sam Edmonds

Comments