Standstill at the World Trade Organization

Standstill at the World Trade Organization

Celebration is likely to be muted when the World Trade Organization (WTO) commemorates its 20th anniversary: the world trade body is in the midst of an identity crisis.

The WTO is the architect of world trade.When it was founded in 1994, and started work on January 1, 1995, expectations were high: Trade barriers were bound to fall, protectionism was to be limited and access to markets was to become easier for developing countries.

That's not how things turned out, however.

Political quarrels, inflexible structures and rapid progress the organization wasn't prepared to respond to in a timely fashion have rendered the WTO a relic of old times. "The WTO is a medieval organization," former WTO director general Pascal Lamy noted in 2003.

More than 10 years later, the WTO has still not made any headway, but is trailing globalization and fighting for credibility. What on earth went wrong?

Neglect

There have been quite a few achievements in the WTO's 20-year history, but the list of failures seems to be longer. For the most part, the organization's problems are homemade.

"The WTO hasn't managed to adapt its regulations to new challenges, because the members aren't willing to change the organization's structure," says Christian Tietje, who teaches international business law at Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg. The principle of unanimous agreement in particular robs the organization of any freedom of action. The WTO charter stipulates that decisions can only be taken unanimously - a Herculean task in view of the organization's 160 member states.

Perhaps that is the reason world trade law hasn't appreciably developed over the past 20 years, "which is certainly not true for world trade," says Achim Rogmann, professor for international commercial law at the Ostfalia University for Applied Sciences in Wolfenbüttel. It's high time for a comprehensive revision of WTO regulations, he says.

The halting involvement of developing countries in decision processes is a great injustice, Rogmann says, adding that the majority of WTO member states are developing countries. "But they often have neither the expertise nor the resources to really pursue their interests in negotiations."

"The EU and the US only advocate free trade when it serves their interests," says Sven Hilbig of Germany's Brot für die Welt Protestant development service. The leading economic powers resort to protectionist measures to safeguard their agricultural markets from cheaper products from developing and emerging countries, but demand that "those very countries liberalize national markets in sectors where they are more competitive."

Success

At the same time, the WTO is still the only platform where global trade rules are agreed on a international level. It's also a good thing the body has expanded over the years, says Simon Evenett, foreign trade professor at St. Gallen University: "The WTO managed to get important countries like China, Russia and Saudi Arabia on board."

"Dispute settlement is the WTO's key success," Christian Tietje points out. Trade disputes are largely settled "in the framework of legal proceedings" that give even developing countries a chance to force influential industrialized nations to give in. The EU has repeatedly had to adjust trade regulations to WTO rules.

The WTO has also proven it is in a position to contain protectionism – which is after all one of the organization's most important tasks, Achim Rogmann says, adding states didn't wall off their markets in the most recent economic and financial crisis.

Where to?

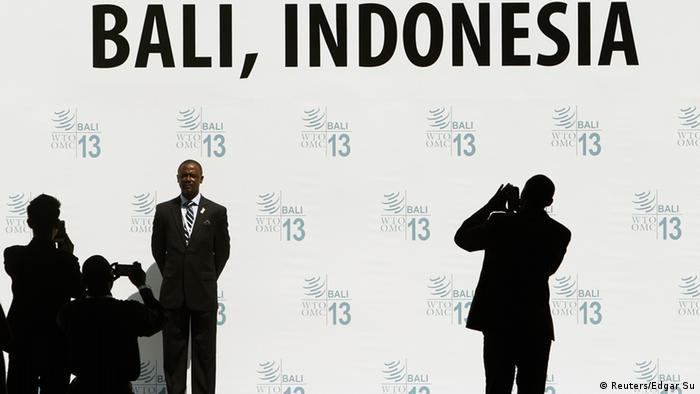

At their conference in Bali in December 2013, WTO member states approved the so-called "Bali Package"aimed at streamlining trade. It was the first comprehensive pact since the organization's founding, and duly celebrated as a breakthrough, a ray of hope - and a saving grace for the organization. "The members showed that they are prepared to keep the WTO alive after all, even in difficult situations," Tietje says.

Simon Evenett takes a bleaker view of the WTO's future. "The success in Bali was a step forward, but it quickly became clear the WTO doesn't want to build on that momentum," he says. "The states aren't ready to agree to compromises that would make the WTO operational."

To regain credibility and continue to play an important role in international trade, the WTO would need a new approach, and possibly new structures and decision-making procedures. It is quite unfortunate that a majority vote can only be agreed by a unanimous vote, and that isn't on the horizon. "There is no alternative to unanimity - none of the great powers will ever accept being outvoted," Evenett concludes. bbc

Comments